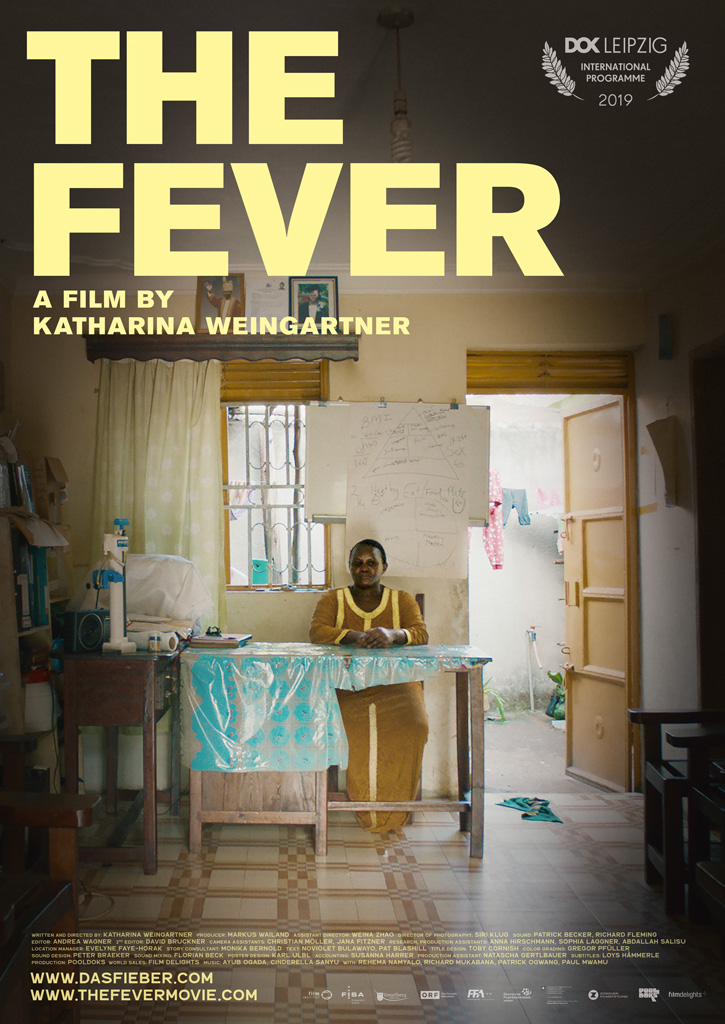

herbal practitioner in Masaka, Uganda.

The single mother of three kids runs a little clinic in her hometown. She works relentlessly to spread the knowledge about how everyone can grow the herb Artemisia annua at home and prevent their families from getting malaria.

professor of biology at the University of Nairobi, Kenya.

After studying mosquitos in the Netherlands and the US, Richard returned to Kenya in order to find ecological and local remedies against malaria. However, he soon realized that research grant donors like the Gates Foundation have no interest in supporting community based low-tech solutions and African scientists.

"We are nothing but field workers, porters. It´s a form of neo-colonialism."

pharmacologist at Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Uganda.

Patrick conducted a clinical study on a flower farm next to Lake Victoria with over a thousand workers about the efficacy of the herb Artemisia taken as tea. The result: malaria cases were reduced by 85%. He has proven that Artemisia could save millions of Africans - if Big Pharma would finally stop pressuring the WHO in banning its use.

“When I started this study about malaria prevention I was warned by many people. That I might get killed by those who profit from the drug.”

teacher in Nyabondo, Kenya.

Almost all the kids in his class have lost a family member to malaria. He educates them in prevention methods but financial struggles in many families make it impossible for lots of students to take care of health problems.

“We don’t have enough food. Most of them suffer, but their parents would rather look for something for them to eat than to take them to hospital.”

One dead child every minute – this stark equation is the toll that Malaria is still taking in Africa. The parasite Plasmodium falciparum is transmitted by mosquitoes and mostly finds its victims among children, while a global industry is attempting to control this epidemic. Katharina Weingartner takes us in her film, The Fever, to an area that she calls the “ground zero” of malaria: the countries around the Lake Victoria basin in East Africa. In Uganda and Kenya she found people who have taken action against malaria using local strategies. The plant Artemisia annua, for example, contains an active ingredient that – when made into a tea – enables the immune system to deal with an infection.

Rehema Namyalo is an activist who has dedicated herself to raise the standing of traditional herbal medicine. She has to battle prejudice that appeared with colonialism in Africa: herbalists were considered to be witches by Christian missionaries, herbal treatment therefore criminalized. But their own governments do not act much better: Rehema argues eloquently that the authorities in Kampala and Nairobi rather work with global pharmaceutical companies - for tax reasons - than with their own people.

The Fever reveals the international connections that determine the fate of so many impoverished patients: a pharmaceutical company such as the Swiss firm Novartis defends their market for the most popular malaria medication; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has invested heavily in a company´s (Glaxo Smith Kline) vaccine that doesn’t work; the World Health Organisation (WHO) uses their approval process to direct the distribution of medicines, often to the benefit of Western companies. Following the logic of economic expansion, African governments have made health into a product. “Something always feeds back into the system,” is how the situation seems to the local people.

Katharina Weingartner reveals these connections strictly from the perspective of the local people. Although she is European, and her film is a co-production of three German-speaking countries, she has managed to avoid all the usual patterns: she is not one of the army of Western “experts” who see Africa as a case that can be “treated” using rationality, technology and economic strategy, repeating and cementing the colonial power dynamics of the past.

Weingartner is changing sides based on principle and feminist solidarity. Along with Rehema, she also accompanies people like Richard Mukabana, a scientist who in the rice fields of Kenya uncovers the damp conditions that are ideal for the transmission of malaria. It was the British colonial rulers who brought rice cultivation to Africa. In another location it is a sugar cane company that has destroyed the rain forest with their monoculture production process, which gives the spread of the fever a boost. Additionally, the science is being done almost exclusively in developed countries: “We’re just field workers,” Richard Mukabana complains, making it plain that he would prefer the fight against Malaria to be directed locally, not without the involvement of Africa.

Unfortunately, there are huge economic interests working against this: mosquito nets are made in Tanzania by a Japanese chemicals company, which destroyed the local market and is creating insecticide resistant mosquitoes. One of the most gripping excursions in The Fever takes us to China. There Katharina Weingartner meets a nobel prize laureate who way back in 1972 had determined that artemisinin was the most important active agent for use in fighting malaria. The WHO was reluctant to include the medicine on the list of approved malaria drugs for 30 years, even though it was considerably more effective with less side effects.

The Fever makes stops in Seattle, Basel and Beijing, but the actual research is done in Africa. Among women who have lost six of their twelve children to the fever, among primary school teachers who teach the children how to recognise malaria, in the forest and bush landscapes where the healing plants grow.

Patrick Ogwang, a pharmacologist, sums it up as follows: “If we free Africa from malaria, we free Africa from poverty.” The Fever sketches out a possible route to this freedom, and to a change in Western aid policy. It also offers a different view of African history, because malaria is in no way a force of nature, it is a phenomenon that was “made natural” through changes brought by colonialism. At least there is now hope that it can be fought using natural means.

How did you decide on the complex themes which are addressed by Das Fieber?

On a journey to Saigon I found a passage in the guide book about Artemisia annua, a plant from the same family as mugworth. It said this was a Chinese herbal malaria remedy that could well have been the reason Vietnam won the war. If that’s right, I thought, then this is a good subject for a movie. But I had no idea where this idea would take me.

How did you find out more?

At the start we were most interested in the relationship between tropical medicine and colonial wars of conquest: Would the colonisation of Africa – apart from the coastal region – even have been possible without the oldest malaria medication, quinine? The European soldiers, missionaries and farmers died in huge numbers while the local inhabitants were immune from the age of five. It was like the parasite was an important defence against invaders.

You also discovered just how significant malaria is to international politics.

Mao and the Americans were locked in a decades long arms race in malaria research. The Vietnamese president Ho Chi Minh asked Mao for support during the Vietnam War, but he didn’t ask for weapons, he asked for malaria medication.

In 1972, Tu Youyou, who later won the Nobel Prize, and her team extracted the active ingredient artemisinin from the herbal compound artemisia annua or sweet wormwood. It is till the most effective malaria medication.

The West was not prepared to allow China to have a lead in this field unopposed. At that time people already knew about resistance to the most common contemporary medicine, chloroquine, and that it was only a matter of time before a huge epidemic broke out. Before 2000, many millions of Sub-Saharan African people died, nobody knows for sure how many.

The film keeps coming back to its core theme of Artemisia annua, a herbal alternative. What is so special about it?

Artemisia is a herbal remedy employed all over the world, and is used for lots of purposes in China. A closely related medicinal herb, Artemisia arfa, is found across the whole of Africa, and is an ancient malaria medication. It basically grows in any location, no matter how barren.

As the expert on herbs, Rehema Namyalo, so eloquently explains in the film, artemisinin is just one of 240 active ingredients in Artemisia annua. The parasites that survive contact with it become resistant because they have only been exposed to one active ingredient. There are two in combination medicines such as Coartem, an ACT. It’s child’s play for malaria parasites.

Novartis knows this very well, and denies it. The WHO knows it, but says there is still no resistance in Africa. There is going to be a medical catastrophe in the near future because there is still no other medicine.

Another problem seems to come from the underlying pattern of West African politics relating to health: it is too technocratic.

The great downfall of technocratic institutions is that basic health services are decimated. The research contracts go to the West, while African researchers are only allowed to contribute material. “We are nothing but field workers, porters. It’s a form of neocolonialism,” says Richard Mukabana, Professor of Biology at the University of Nairobi.

Why have you had your sights on Bill Gates and the Gates Foundation for so long?

We had planned to interview Bill Gates for years. He and his money are the secret rulers of the malaria world. As the biggest private donator to the WHO, he determines global health policy. In 2008, the Gates Foundation boasted at a press conference that malaria would be wiped out by 2015. There is no longer any trace of this promise on the Internet. The world of malaria research simply laughed at them. Nobody is laughing anymore, because now there is no way of avoiding Gates.

Eventually we realised that we were no longer interested in these big words, even though the media is full of it. We wanted to unambiguously be on the side of people who actually have to live with malaria, battle against it, unseen and unheard by anyone. They should be allowed to shape their own fate. So we felt it right to simply present silent images of the robotic world of glass palaces, in part funded by their suffering and the death of their children. The Novartis Campus in Basel is, like the Gates Foundation in Seattle, almost made for the camera, to show the contradiction.

Why in the end did you decide against telling the story from a western perspective, as your German and Swiss coproducers wanted you to do?

You still see the same old postcolonial patterns in a huge number of documentary films, where Africa is used only as a backdrop. With a complex subject like malaria, the temptation was to concentrate on all the scandalous global interrelationships. This is what the Global North is used to seeing, but the people impacted by malaria would once again have been seen as victims and statistics. It is absurd that 90% of research money stays in North America and Europe when 90% of actual cases of the disease are in Sub-Saharan Africa. Those effected are rendered voiceless and refused the medicine they need. It was important to us that our protagonists, who have to live their whole lives with the malaria parasites, were presented as self-reliant actors who want to and are very able to battle the illness for themselves.

Screenings

23.09. 19:00 Uhr Düsseldorf, Filmkunstkinos, DE | 25.09. & 26.09. Humans of Film Festival, Amsterdam, The Netherlands | 13.10. 19:30 Uhr, Star Movie Ried, Tumeltsham, AT | 23.10. 20:00 Uhr, Kino im Emailwerk, Seekirchen, AT | 27.10. 18:30 Uhr, Festival des Libertés, Bruxelles, BE | 03.11. Weltfilmtage, Thusis, CH

Cinema Dates in Austria

Stadtkino Wien | KIZ Royalkino, Graz | Volkskino Klagenfurt | Leokino, Innsbruck | City Kino Steyr | Village Cinema, Wien | Cinema Paradiso, St. Pölten | Moviemento, Linz | Kino Freistadt | Admiral Kino, Wien | Stadtkino Center Ternitz | Actors Studio, Wien | Lichtspiele Katsdorf | from 9.10. Kino im Kesselhaus, Krems | from 23.10. Top Kino, Wien | 29./30.10. Stadtkino Horn | from 24.11. TAS, Feldkirch | 3.12. Kolpingsaal, Bruneck | 5.12. Spielboden Dornbirn | 9.12. Star Movie, Ried

Bozcaada International Festival of Ecological Documentary 02.-08.11.2020 www.bifedonline.org

Explanation of the jury: The grand prize given on behalf of Fethi Kayaalp in the Main Competition category of BIFED 2020 was won by Katharina Weingartner's movie "The Fever". Because it portraits with craftsmanship and excellent filmmaking skills, a pressing and relevant issue that affects and kills hundreds of thousands of women, men and children every year. The empowerment of people and women, through different medicinal techniques, as opposed to occidental, capitalistic and multinational medicine corporations, takes place in this film, shedding light on how this alternative methods are a key for autonomy of health resources, science and land sovereignty. This films aims to show the attempts to break the chains on several levels of oppression, colonization and economic violence.

04.09. 16:30 Uhr, Seefeld (Q&A)

04.09. 19:30 Uhr, Seefeld (Q&A)

05.09. 18:00 Uhr, Gauting (Q&A)

04.09.2020, 19:30

24.09.2020, 19:00 Uhr

05.08. 2020, 8 pm Introduction with Prof. Dr. Stefan Schubert (former head of the Department of Infectious and Tropical Medicine at Leipzig University Hospital) and then discussion with Katharina Weingartner

10th of March 2020 20:30, Atlas - Large Hall Sokolovská 1, Prague 8

11th of March 2020 17:30, Evald Národní 28, Prague 1

25th February, 5.00 pm Q&A with Katharina Weingartner

1st March, 4.00 pm

Building Infrastructures for Social Impact Movies on the African Continent

24th February, 12.00 Simon Inou and Katharina Weingartner

Weltpremiere 01.11.2019 Q&A mit Katharina Weingartner, Weina Zhao, Dr. Pierre Lutgen und Dr. Jérôme Munyagi

OKTOSCOUT, Wednesday, 14.10.2020

THE FEVER Special Screening "Call to Action" at Stadtkino, Vienna

Covid-19 has put the world on hold. But with Malaria, which has killed more people than all other diseases and wars on Earth combined, it ́s business as usual, or even worse: Deaths are expected to double due to the lockdown in African countries. The Fever portrays the fight against malaria in East Africa as a case study in greed, courage and self-determination. After the movie screening panel discussion with Louise Deininger (African Conceptual Artist, Author, Leadership Coach), Dr. Sheron Dzoro (Medical Scientist) and Katharina Weingartner (Director THE FEVER). Moderator: Otalia Sacko. Editor OKTO: Shoshana Rae Stark

„The Fever" dares to look beyond conventional medicine and finds deeply impressive stories about the power of struggling to find solutions to one of the biggest health problems on earth.

A dense, exciting didactic play

Falter

An urgent, necessary film.

Katharina Weingartner brings to light grievances that should be discussed urgently!

A docu-thriller that exposes the global players in the business of fatal fever

Kronen Zeitung

The self-confidence and stubborn courage of the African protagonists of "The Fever" give the documentary an impressive impact!

"The Fever" is a beautiful film about a horrific disease and about the continuation of an outrageous colonial story.

Thanks to the thorough research and plausible narration, the daring thesis becomes a shattering certainty in the course of the film. An almost unbearable, but in any event indispensable film.

The madness of colonial heritage. A journey into the heart of pharmacological darkness.

"The Fever: The Fight Against Malaria" is committed and superbly researched, but above all one thing: harrowing in its message. Not only important, but really good.

"The Fever" stimulates a long overdue discussion about the business of life.

Download Still © pooldoks

Download Still © pooldoks

Download Still © pooldoks

Download Still © pooldoks

Download Still © pooldoks

Download Still © pooldoks

Making Of Still © Jana Fitzner, pooldoks

Making Of Still © Jana Fitzner, pooldoks

Making Of Still © Jana Fitzner, pooldoks

Making Of Still © Jana Fitzner, pooldoks

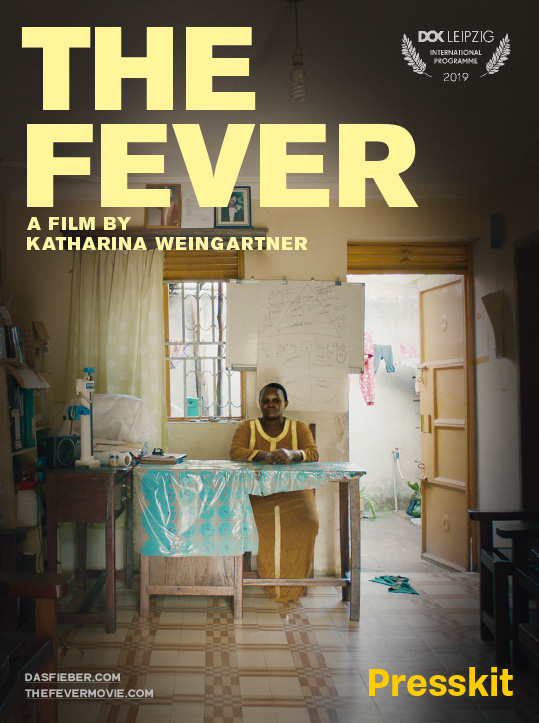

Download Poster © pooldoks

Download Presskit © pooldoks

Katharina Weingartner © Heribert Corn

pooldoks filmproduktion

Redtenbachergasse 15/2A

1160 Vienna, Austria

+43 1 9477688

office@pooldoks.com

www.pooldoks.com

apomat* büro für kommunikation GmbH

Mahnaz Tischeh

Neubaugasse 25/1/10

1070 Vienna, Austria

+43 699 1190 22 57

office@apomat.at

www.apomat.at

filmdelights+

Lindengasse 25/10

1070 Vienna, Austria

+43 1 9443035

office@filmdelights.com

www.filmdelights.com

W-film Distribution

Gotenring 4

50679 Köln, Deutschland

+49 221 2221980

mail@wfilm.de

www.wfilm.de

Press contact Germany

Senta Koske

+49 221 2221992

senta.koske@wfilm.de

Cooporations contact Germany

Katrin Glados

+ 49 221 83008350

katrin.glados@wfilm.de

2021 © www.pooldoks.com